A Rare and Joyeous Alchemy

Fred Otnes at Reece Galleries; Selina Trieff at George Billis Gallery; Peter Hoffer at Kathryn Markel Fine Art

By Maureen Mullarkey

ALL HIGH ART ORIGINATES IN THE PLAY between organization and intuition. Fred Otnes brings to his collage paintings a classical refinement and control that makes poetry out of chance pictorial effects. He dips into early Cubist collage techniques, touches Florentine and Renaissance bases and reverses Dadaist chaos into gorgeous homages to order. This mini-retrospective displays a rare and joyous alchemy.

|

| Fred Otnes |

Born in 1930, Mr. Otnes served his first apprenticeship working after school at a local Kansan newspaper in the engraving department. The experience led to his assignment, in 1947, to a Marine mapping unit which marked his sensibilities for life (an experience similar to Richard Diebenkorn’s). He enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1949 but preferred the hands-on challenges of commissioned illustration.

Mr. Otnes became a major influence among illustrators, moving the field away from traditional representational techniques. His elegant and suggestive solutions to design problems earned him over 200 awards and prestigious commissions. By the 1980s, at the top of his field he decided it was time to devote himself exclusively to the personal compositions he had been creating for years.

With a cunning blend of impulse and rigor, he turns the anti-painting urge of collage against itself by producing images in which the collage elements flow seamlessly into painted ones. Surfaces are distressed until the stubbled texture of old walls emerges to absorb and mute collaged items. Images flood with unpremeditated accidents, unguarded but never unguided.

|

| Fred Otnes |

Snippets of typeface, incantatory photo transfers of calligraphy or mathematical symbols, musical notations, pieces of metal type, dried leaves appear throughout. “The Jester” (1998) is a riot of fragmentary forms that coalesce into a fractured jester — a recurring homage to early Picasso — in his two-horned hat. “Night in the Garden” (1996) represents a Cornellian strain in his work that I particularly love. Mr. Otnes appropriates Renaissance imagery for broodier purposes than Cornell’s. Juxtapositions of darkling figures, foliage and incunabula serve a midnight mood that hints at nightmares contained, for now, by symbols of order: the arches, corbels and moldings of classical architecture.

His sensibility requires a limited, earthen palette. “Blue Figure” (2004) the single painting built on a clear primary color, is the only off-note.

Decades of immersion in the commercial world has exacted a price. Despite the commercial background of many Pop artists of the 1960s, current art world protocols fetishize the now-standard M.F.A. career track. Add to that a celebrity-consciousness that cares more about who makes things than about how they are made, and you have a formula for critical neglect. This is a terrific chance to see what timeless magic Fred Otnes makes with calibrated randomness and deep response to specific moments in art history.

A STUDENT AT THE HANS HOFFMAN SCHOOL in the 1950s, Selina Trieff uses color for the exhilaration of it, creating opulent friezes that whisper of mortality. Ignoring the realist path of most other figurative painters, Ms. Trieff has gone her own way. Her life’s work is a metaphorical, painterly cosmos that unsettles and delights at the same time.

|

| Selina Trieff, Sunlight |

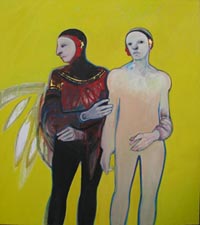

“Red Bird on Her Shoulder” (2006), a tableau vivant with two figures against a brilliant saffron colored ground, typifies Ms. Trieff’s blend of the hieratic and theatrical. Devoid of atmospheric perspective, two figures presented themselves frontally, like tomb sculpture. A length of gold leaf, repeated down the torso of one figure, conjoins them. The red line of a slack rope curves behind them. A bird, part whimsy, part omen — Poe’s raven in blood red — accents the pageant.

These recent paintings, accomplished with characteristic bravura despite the artist’s increased frailty, are simpler in composition than earlier ones. Absent from current repertory are the Jester, the skeletons, the hooded figures and their animal familiars — Ms. Trieff’s whole sepulchral wonderland in which the skull of Yorick contemplated Hamlet throughout her long exhibition career.

Compositions keep to two figures or single heads, each one stamped with the artist’s own features like identical funeral masks. Yet the tone is buoyant, more youthful than the brooding effigies of previous work. Her troupe has shed their Goya-esque robes for acrobats’s bodystockings; her danse macabre has given way completely to a festive stage. Stylized palm leaves, floated behind figures, hint at the wings of Florentine angels. Here and there a halo appears. The entire vivacious ensemble, viewed against long acquaintance with her work, jolts recollection of one mordant Bob Dylan line: “Ah, but I was so much older then; I’m younger than that now.”

PETER HOFFER IS A DEFT AND APPEALING PAINTER who uses landscape as an excuse for pure painting. The motifs of landscape — luminous skies set off by the outline of trees, the dramas of light and shade — provide structure for gestural play, fragile transparencies, and beautiful color effects.

|

| Peter Hoffer, Emblem |

Light is the keynote of his accomplishment. Mr. Hoffer enjoys a pitch-perfect tonal sense that evokes the atmosphere of real places even though he is inventing his own. He invests imaginary scenes with the air, dew and texture of real ones. He does so with great economy and without sacrificing remembered responses to the natural world. Emphasis is on the mood and sweep of his motif, not the incidentals of a locale.

Mr. Hoffer’s color range is seductive, discreet and blessed with complex, convincing greens. Spare, loose layers of pigment are washed onto ungessoed panel, allowing wood grain to suggest the variegated patterning of nature. The most compelling works are those that, like the lovely “Periphery” (2005) and “Emblem” (2006), use the accidents of painting to evoke a sense of place rather than announce the artist’s presence. Finishing layers of clear resin lend optical depth to delicate paint surfaces.

“Fred Otnes: Three Decades” at Reece Galleries (24 West 57th Street, 212-333-5830).

“Selina Trieff” at George Billis Gallery (511 West 25th Street, 212-645-2621).

“Peter Hoffer: Common Ground” at Kathryn Markel Fine Arts (529 West 20th Street, 212-366-5368).

This essay first appeared in The New York Sun, April 13, 2006.

Copyright 2006 Maureen Mullarkey