Sweet May

Drawings and prints by Emily Nelligan and Marvin Bileck at Alexandre Gallery; Jane Piper at Hollis Taggart; Cornelia Foss at DFN

by Maureen Mullarkey

THE MORE YOU ARE MOVED BY PARTICULAR WORKS OF ART, the harder they are to talk about. Work opens to you in silence, like a breviary; you enter it and can only bow to what you find there. Words fail because none correspond to the revelatory power of what you meet within. The poetic intuition on exhibit at Alexandre Gallery is rare.

|

| Emily Nelligan |

For Emily Nelligan and Marvin Bileck (1920 - 2005), art making has been a vocation, a way of being in the world and attending to it with wonder and grace. The couple lived and worked together in northwestern Connecticut and Cranberry Island, Maine, until Bileck’s death this April. In each one’s art, love of the particular yields a hint of transcendence,

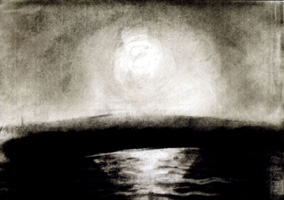

As a young artist, Ms. Nelligan took up charcoal because paint was too expensive. By now, she has so perfected her medium that paint would look paltry beside it. Her drawings can be defined in terms of landscape motifs but that cheats them of their resonating abstract splendor. If the ancient canonical hours could be observed by images instead of prayers, here they are.

Canticles of light, her imagery arises from blacks and whites functioning reciprocally as antiphons and responsories. Morning anthems alternate with lyrical nocturnes; Lauds anticipates Vespers and the night vigil. What else is that luminous form emerging from midnight “22 October 2001” but a call to Matins? Work is dated rather than titled, reminding us that time itself is measured by light. Each drawing is an act of praise and gratitude for the infinite variety of nature and the daily surprises of the visual world.

|

| Marvin Bileck |

Limpid, fine-lined and full of incident, Bileck’s work has a Flemish quality but with details fused by an enveloping atmosphere created by working the plates over long periods, even years. “And Dreamier the Gloaming Grows” (2001-02) and “Uprooted Trees—Ruth’s Woods” (1990) , combining etching and engraving, are exquisite samples of the process. His pencil drawings accent the dancing contours of wild roots, rocks and twisted trunks; subtle caesuras between marks suggest the cultivated dialogue between hand and eye.

Ms. Nelligan is barely known outside a small circle of artists. Her husband, a fine printmaker and distinguished illustrator of children’s books, was somewhat more public; he exhibited in museums around the country. It is anyone’s guess when these works—irresistible in their intelligence and beauty— will be seen again. Do not miss them.

Jane Piper (1916-1991) is a welcome find. Among the generation of artists who studied in Philadelphia with Arthur B. Carles, Piper was considered the most important, an instinctive colorist in her own right. She had her last show at the New York Studio School, the year she died.

The older paintings here, closest in time to her association with Carles and strongest in visible influence, are rich and satisfying. Bold curves and arcs are stopped in mid-flight by a strategic angle or line. Every abstract composition is enlivened by a striking palette of royal blues, turquoise and gold set against lavenders and purples. Piper had an affinity for color harmonies, and the way individual colors changed their personalities according to the ones placed near them. She sought to make the spectrum function musically—a passion Carles acquired from Robert Delaunay and communicated to his student.

|

| Still Life with White Vase, 1942, Jane Piper |

Piper wielded an enviable brush. Every aspect of painting can be usefully taught except paint handling, which owes much to the painter. It is physical and personal —like the character of one’s laugh. In every one of these works, the substance of her paint is beautiful. Colors are put down with broad, sensuous strokes that build next to and atop each other to a kind of perfection we are not accustomed to. Even her 1958-59 homages to the fluttery mark-making of Mercedes Matter—Carles’s daughter and founder of the Studio School—are distinguished by the graceful authority of Piper’s paint application.

As she grew older, Piper’s hold loosened on the shaping influences that revealed her to herself. Later works lack the dynamism of the earlier ones. From the 1970s onward, painting become paler, more transparent; underlying still life motifs became more literal. Kaleidoscopic movement stilled; the intensity of the early work subsided. But paint quality never languished.

The exhibition catalogue contains a fine essay by painter Bill Scott. It is a personal reflection, testimony to the disinterested love of craft that binds one painter to another.

Cornelia Foss’s landscapes are pleasant, easygoing scenes of Long Island’s East End. Too easy. For the sake of one or two paintings, I tried to like the exhibition better than I really do. Excepting “Winter Tree II” (2005), with its pronounced accents and clear compositional orchestration, too much appears halfhearted. The lukewarm quality overall leaves you wondering what animated these sights for Ms. Foss. Desultory paint application, tepid contrasts, irresolute drawing, and absence of nuance within color zones leave you no compelling reason to pay attention. “June” (2004) looks to have been painted from Jane Freilicher reproductions.

Good landscape painting renders the artist transparent. It draws you away from the artist and into the light and terrain of the phenomenal world. Here, we are still lounging on the verandah, drink in hand, watching Ms. Foss turn a viewfinder on her surroundings. The sand, the surf, the view across the lawn. How nice to be in Bridgehampton this time of year.

“Marvin Bileck and Emily Nelligan: Cranberry Island, Drawings and Prints” at Alexandre Gallery (41 East 57th Street, 212-755-2828).

“Jane Piper: Poetic Distillations” at Hollis Taggart (958 Madison Avenue at 76th Street, 212-628-4000).

“Cornelia Foss: New Paintings” at DFN Gallery (176 Franklin Street, 212-334-3400).

These reviews first appeared in The New York Sun, May 26, 2005.

Copyright 2005, Maureen Mullarkey