Janet Malcolm / Susanna Coffey

Smart collages at Lori bookstein Fine

Art; Vacant painting at Tibor de Nagy

By Maureen Mullarkey

AS A CHALLENGE TO TRADITIONAL PAINTING,

collage is one of Modernisms lasting gifts. Argus-eyed, it endows

its audience with a kaleidoscope of viewpoints along a scale

from the personal and recondite to the purely formal. It is

an art of association and surmise, its graphic symbols hinged

to a range of experience that is as varied as the audience that

looks at them.

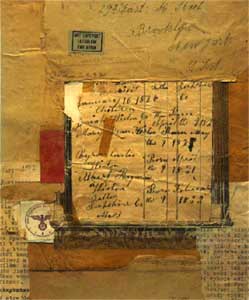

Janet Malcolm handles the medium with the same attention to

nuance, the same passion for exactitude that informs her writing.

What becomes apparent in this exhibition is that a writer's

eye for telling details is quickened by the same nerve that

excites pictorial intelligence. The aim of both is to get it

right. Malcolm's journalism career began with articles on interior

decoration, design and photography. The visual preceded—and,

throughout her working life, informed—everything.

|

| Janet Malcolm Untitled 2001

|

This is beautiful and serious work, poised in a solitude all

its own. It comes after twenty years of engaging papier collé

for her own pleasure. On view are thirty-three collages.

Some originate in the rigor and self-effacement of Russian avant

garde sensibility. Others, more fluid in form, depend on the

graphic power of objets trouvés, a quarry of

fragments mined for visual and associative effect. There is

a Surrealist edge to certain ones that is carried off with great

aplomb. The ensemble orbits around Malcolm's long-held attachments

to literature, psychology and art.

Her reservoir of objets trouvés leans toward

the familial: the paper trail of a family history and its intellectual

life. But biography is not the subject of this exhibition. Every

artist reaches, psychologically or in fact, for those things

closest at hand. In the end, what matters is not the artist's

experiences but her capacity to transmute private responses

into forms that speak to strangers. Malcolm's work speaks eloquently

of the life of the mind and its capacity to civilize, order

and interpret the confusion of the lived life.

Vladimir Tatlin, heady with art's appointed mission in 1920,

declared his distrust of the eye. But Malcolm, an attentive

student of Kurt Schwitter's genius, is careful to give the eye

its due. Her attraction to hallmark Constructivist designs seems

true to her own temper which, on the evidence here, is both

reserved and austere. There is a structural composure—a

calm—to these compositions that calls to mind that other

acolyte of Kurt Schwitters, the lovely Anne Ryan.

Malcolm, like Ryan, chooses her floating fragments with a keen

eye for texture and color. The works of each woman are on an

intimate scale and convey an illusion of confidentiality. They

suggest something sequestered, revealed behind closed doors

to just the two of us. This is particularly true of Malcolm's

inclusion of old handwritten items. We respond to these stimuli

in quite personal ways. They are catalysts of memory, her remembrances

triggering our own. Acknowledgements of a human presence, they

have the impact of letters from the dead.

Typography, where it appears, is chosen as much for its architecture—the

weight , balance and magic of alphabets—as for signal

value. Ryan jumped the boundaries of language, thoroughly subordinating

the connotative aspect of printed stuffs to her palette. Malcolm,

by contrast, has spent a life time using language as an instrument.

She naturally retains and exploits verbal associations. Her

selections mean what they say. An entry ticket to Cezanne's

atelier is intended to a be recognized for what it is. A scrap

of a letter typed on an old manual typewriter serves its design

purposes while it remains a sly but deliberate reference to

Schwitters.

The floated faceting of these collages is subtle, elegant,

many of them witty. But one particular image, titled Son,

chilled me. A photo of an old crib hovers, weightless and off-axis,

over a splayed black ground. The metal crib, on casters, is

institutional, shorn of bedding or any suggestion of nurture

and comfort. It stands empty in a space barren as any barracks.

Here is an image of cold containment, pragmatic, unyielding,

more suited to prison than the nursery. A cage. Given the time

frame suggested by the age of the crib and the black and red

Constructivist surround, it is impossible not to see it as an

icon of detention and deprivation. The image is freighted with

a weight that has not lifted since the 1930's.

Malcolm's artistry is consistent with the restraint, discipline

and regard for object, rather than process, which characterized

early Constructivist work. Her temperament respects control.

And control slips only once.

The oversized America 1950 is predictable feminist kitsch.

A catalogue of male portraits smile at us from annual reports

circa late 40's. The single female face is shrouded, as if in

purdah, by a piece of vellum. The whine is almost audible: women

are exiles in a man's world. Coming from Janet Malcolm—no

outsider, she—it seems disingenuous. The piece indulges

in the reflexive, approved disdain of a politicized present.

Besides, Malcolm's Dadaist models took aim at their contemporaries.

Anybody can kick a decade long finished.

But false notes have their uses, if only as reminders that

art is measured by what it rejects as much as by what it embraces.

There is an elegiac quality to this work that extends beyond

the personal. Without necessarily intending to, it bears witness

to the illusional character of its antecedents. Art's contra

mundum stance in the opening decade of the twentieth century

has not brought down the house. In art, radical breaks heal

over and yesterday's daring become today's decor.

There is a lesson in Malcolm's gravitation toward Constructivist

design principles that extends beyond their appropriateness

to family history. The formal achievements of a previous age

remain alive and enlivening to those who respond to them. It

is the dead hand of the present that has to be feared.

Lori Bookstein Fine Art, 50 East 78th Street,

New York NY 10021 Tel. 212.439.9605

SUSANNA COFFEY IS A GIFTED PAINTER AND

A REPELLENT ARTIST. I love her paint—her hand—but

can not stand looking at her work. She has no subject matter

that extends beyond her own narcissism. The focal point of every

canvas is her own head, relentlessly fixed to the central axis.

And an unpleasant head it is: brash, assertive in its sourness,

a little crude. So much knowledge about the character and behavior

of paint, such a keen eye for color, exquisite tonal control,

surfaces to die for—all of it adding up to … to

what? It is the Cindy Sherman script done up in oils. Smart-ass

exhibitionism for the uptown trade.

|

| Susanna Coffey Self Portrait (Eris)

2003 |

Susanna Coffey lit from below. Susanna Coffey lit from behind.

Susanna Coffey in drag of one kind or another. Susanna Coffey

in a baseball cap turned backwards. Susanna Coffey in the same

cap straight up. Susanna Coffey in a bathing cap, maybe. Susanna

Coffey in eyegear with sparkles. Without sparkles. Susanna Coffey

with a blue butterfly stamped on her forehead. (Sorry, that

was last time. It all blurs together.) This year's line-up reaches

for social significance with three views of Susanna Coffey against

a backdrop suggesting some holocaust or other. But which one?

Don't ask. It is only the pose that counts.

I can see the next exhibition already: Susanna Coffey and the

Staten Island Ferry; Susanna Coffey and the Gaza Strip. Susanna

Coffey and the rockets' red glare. You get the picture.

This year's exhibition includes one wall of small, identically

sized [5 x 10 inches] flower paintings. More casually brushed,

lacking the luscious surface depth of her signature self-portraits,

they almost seem to have been painted by someone else. Each

flower stalk—here a rose, there a tulip or bird-of-paradise—lies

lengthwise in obedience to a display formula. The cookie-cutter

format suggests commercial convenience. At $3,800 each, these

are intended for the shallow-pocket collector who wants a Susanna

Coffey but won't pay up for the real thing.

In a pre-emptive move to deflect the obvious, anticipated criticism

of Coffey's head show, Mark Strand plays offense by asserting

that her parade of heads reveals the difference between subject

matter and content. Each of these faces ("a record of its

own emergence") is not guided by likeness but represents

rather "the creation of a painting self."

Nice try, Mark. But this is one of those counterfeit distinctions

that come in handy for catalogue essays. And it sidesteps the

issue of why anyone should care whether what emerges from these

files is Susanna Coffey or the Cheshire Cat . The "painting

self" is the living woman who sets out her palette while

she finishes a second cup of coffee and reminds herself to call

the dentist before lunch. What appears on canvas is no self

at all. It is a construction, a self-referential fiction with

no plausible reference to anything past range of a deadening

solipsism.

To his credit, Strand limits his catalogue blurb to one paragraph.

That in itself is refreshing but certainly appropriate here.

There simply is not that much to say. And it is discouraging

so see a large gift put to such small purpose. These heads are

indeed records—of the banality and absence of conviction

that afflicts so many of even the best contemporary talents.

Tibor de Nagy Gallery, 724 Fifth Avenue, New

York 10019 Tel. 212.247.2111

This review also appears on ArtCritical.

Maureen Mullarkey � October, 2003