Bodies Tumbling After the Fall

Kiki Smith’s 25-year retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art

By Maureen Mullarkey

DOYENNE OF SECRETIONS AND SPARE PARTS, Kiki Smith offers a field guide to the confusions of late modernity. Her traveling 25-year retrospective is littered with the paraphernalia of neo-pagan feminist spirituality. All the ingredients of spellcasting and other womanly arts are here: sperm, mucus, saliva, entrails, a few bird carcasses. Body functions and innards are trumpeted, dead-pan, as “a discourse of the meta-body” or “metaflesh” by critics. The exhibition takes us back to smoking cauldrons and recipes from that 1980s primer “The Holy Book of Women’s Mysteries.”

|

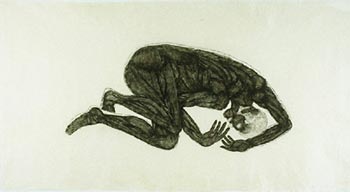

| Kiki Smith, Sueño, 1992 |

The daughter of famed American sculptor Tony Smith, Kiki grew up helping in her father’s studio. She dropped out of Hartford Art School in 1976 and decamped to New York. It was the heyday of the Feminist Art Movement, an era that left a dispiriting stamp on her work.

The problem is not with her subjects — mortality, decay, corporeality. The problem is crudity of conception and, frequently, execution. Facile nihilism runs the body shop. Searching for the nature and purpose of man? No point looking in a rib cage marked “VOID, OF COURSE.” Try the urogenital or digestive tract nearby. Nature mysticism gone sour (“NATURE DOESN’T CARE IF YOU BECOME FLY FOOD”) is as deep as it gets.

Workmanship is uneven, depending on whether a particular work relies on historical antecedents, collaboration, or the artist’s unguided fancy. Drawing, which reveals her hand most intimately, is so raw that it corrupts trust in her capacity to achieve, unaided, formal grace in any medium. Her indeterminate crinkled paper constructions suit an unsteady hand.

Craft is self-limiting but Ms. Smith’s materials are all over the map. Her welter of mediums forages for an external, technical solution to problems of intuition: “I made things out of bronze for a while. I tried to make them out of concrete, and then I just thought, "F**k it!" I didn't like that.” There is a lot she did not like.

Accompanying essays by Linda Nochlin and Marina Warner emphasize “the fundamental role of Catholic thought in her work.” But her fundaments are rickety. As she told the Journal of Contemporary Art: “There's something Aquinas said about form being separated from matter, which is an underlying concern in my art. A lot of my work is about separating form from matter and kind of seeing what you've got.”

The muddle has just enough pretension to pass as an intellectual statement. But, clearly, Ms. Smith does not grasp the great philosopher’s concept of form. She mistakes it for mere shape. (If ever she manages to separate form from matter, call me.)

Superficial demi-Catholicism provides fodder for art that mimics religious iconography (e.g. images of the Virgin Mary) but is empty of religious sensibility. Ms. Smith has more in common with New Age covens than Catholic culture. A vehicle for feminist grudges, her inverted iconoclasm bears malice toward shared cultural possessions. Not even Little Red Riding Hood escapes vandalism.

The Whitney show is a strangely sanitized retrospective that omits key works. Three signature beeswax sculptures are conspicuously missing: “Tale” (1992), a crawling female figure who extrudes ten feet of excrement; “Pee Body” (1992), a woman squating over a trail of urine; and “Train” (1993), a standing woman menstruating across the floor. Because these cannot be ignored, they are celebrated in the catalog and occupy a prominent place in Nochlin’s and Warner’s commissioned endorsements.

Ms. Nochlin solemnizes the defecating “Tale” with reference to “Lives of the Christian Martyrs,” saints legends, the annals of Amnesty International and medieval altarpieces. Ms. Warner finds analogies to Ovid, Baudelaire, Jean Piaget, et alia, in such “incarnational imagery.” Ms. Nochlin relates the “yucky substances” of “Pee Body” and “Train” to the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. She asks: “Why can’t piss and menstrual blood be transformed into jewels,” just like bread and wine? Ms. Warner proclaims: “All flesh is resurrected through her art.” Gloria deo.

To a culture in free fall, things mean whatever you want them to mean. Nothing inheres. Dignity has no foothold. In reality, of course, there is such a thing as indecency but shallow intellection covers for it. So do curators who do an end run around the vulgarities on which Ms. Smith’s notoriety stands.

“Blood Noise” (1993) commemorates the death from AIDS of the artist’s sister. The woman’s symptoms (“CONSTIPATION,” “BLOOD IN URINE”) are clumsily lettered on streamers in a mawkish valorization of victimhood. The piece is rigged to compel pity, insulating itself from aesthetic appraisal. We cannot judge the art without seeming to judge the sufferer.

A weakly modelled bronze statue of “Lilith” (1994) creeps down the wall like a water beetle. Adam’s upstart first wife in medieval fable and feminist mythology, she is meant to make you feel feisty and defiant of patriarchal hierarchies. But go-it-alone Lilith is an inapt heroine for an artist whose reputation is inseparable from her father’s legacy. Nevertheless, the ideology of victimization requires the planet’s most privileged daughters to portray themselves enchained.

A repulsive Mary Magdalene” (1994), covered with hair, drags a broken leg shackle “as a symbol of emancipation.” (From what? Her trust in the good and true?) Ms. Nochlin smiles on the artist’s urge to “undercut the traditional dignity” of biblical women with unpleasant surface effects. Resentment loves a wrecking ball.

No hint of self-parody relieves the juvenility of “Pieta” (1999). The artist scratches out a portrait of herself in the attitude of a Mater Dolorosa mourning a dead cat. Her drawing is too feeble to support the frisson of bad-girl impudence; intention collapses in debility.

“Virgin Mary” (1992) appears as a bloody, flayed anatomy model. A stranger to the inner dimensions of Marian typology, Ms. Smith takes predictable aim at a figment of her own callowness. She misreads the historic hold on Western imaginations of this unlettered, Jewish peasant girl from the sticks of Galilee under Roman occupation. Miryam of Nazareth, embodiment of the biblical dialectic between divine initiative and human will, has motivated exalted Western and Byzantine art. Ms. Smith, uncomprehending, can only despoil.

To Whitney trustees, themselves world-class collectors of contemporary art, Ms. Smith’s name is a currency voucher redeemable for cash at auction. You can’t help but think that nothing keeps auction prices up like a retrospective buttressed by credentialing essays from celebrity scholars. Even if (or especially if) pivotal works are coyly omitted.

Through November, Pace Prints extends the Smith brand with an offering of porcelain figurines, manufactured in multiples from the artist’s designs. Sister Mary Innocentia Hummel, a young Franciscan, originated a line of trademark porcelain figures. Ms. Smith follows with more tchotchkes for the coffee table. Are figurines a Catholic thing? Does Pace know?

G.K. Chesterton wrote that when a great faith disappears, its sublime aspects go first. It follows, then, that a culture once sustained by all that derives from the sublime dwindles with it. Meanwhile, art gropes in the dark for something larger than itself, guided only by its own spoor.

“Kiki Smith: A Gathering, 1980-2005” at the Whitney Museum of American Art (945 Madison Avenue, 212-570-3676).

“Kiki Smith Multiples” at Pace Prints (32 E. 57th Street, 212-832-5162).

This review first appeared in The New York Sun, November 16, 2006.

Copyright 2006, Maureen Mullarkey