Matter-of-Fact Still Lifes & The Last Man Standing

Victor Pesce at Elizabeth Harris Gallery; Charles Seliger at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

by Maureen Mullarkey

WE TAKE STILL LIFE PAINTING FOR GRANTED much as we assume prose is the natural way to write. Victor Pesce’s prosaic means remind us that still life, like prose itself, is not an instinctive genre but an invention. His unadorned, seemingly matter-of-fact approach is an artful alternative to that cultural commonplace, the table top piece.

|

| Phantom II, 2004, by Victor Pesce |

Mr. Pesce’s still lifes concentrate on those elements of decision making that underlie the apparent “natural” order of things. An attentive student of Georgio Morandi, he builds his compositions on spatial conundrums in which scale and measure are crucial. Like Morandi, he establishes no hierarchy among objects or between things and the space around them. Presence and absence are equal partners in his picture-making. By renouncing sentimental associations attached to objects, the artist creates a sense of geometrical order that rewards sustained looking.

One or two bluntly delineated, intelligible forms — a pair of bottles, a few boxes — present themselves with succinct austerity. Mr. Pesce chooses items for their architecture, minimal physical presences divorced from association with consumption or the glow of possession. Human uses are irrelevant. Essential forms — cylinders, cones and squares — are explored for their own sake. Only accidentally are these bottles and boxes. Topological survey, conducted with detachment, takes precedence over fond depiction or narrative.

In “Two Bottles on a Shelf,” a brace of same-sized bottles is painted to retard reflection, forcing concentration on contour and bulk. The double silhouettes, viewed straight on, convey dimensional reality with the barest of details: a slight curve at the lip and shoulder formed by the bottle mold. Color enhances the spatial game. The dominant color, a bold blue, becomes surprisingly recessive when placed against a background of the same value. In this deceptively innocent composition, it is the paler form that asserts itself by contrast. If Mr. Pesce’s pictorial moves are modern, his composure and reserve are classical.

Mr. Pesce observes motifs from different angles and under different lighting conditions; he records the effect of different color and tonal schemes on not-quite identical compositions. “Phantom I” and “Phantom II” (both 2004) presents the same long, slender object tightly wrapped in a paper bag that twists to close at the top. One version is rendered in bleached, fresco-like tones that unballast the image, lending it a certain cool weightlessness. Temperature rises in the second version, the deepened color seeming to intensify the density of the very same object. “Phantom II,” with its delectable surface and subtle double-shadow, represents the kind of curious beauty and solemnity Mr. Pesce achieves.

|

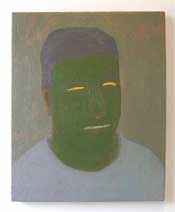

Smiley, 2005, by Victor Pesce |

The artist’s pictorial intelligence makes all the more disconcerting the strange heads, such as “Smiley” (2005) and “Lad of Athens,” (2006) introduced here. The off-beat color sense that enlivens his still lifes turns lurid applied to a human visage. All materiality is gone. Flat as targets on a shooting range, these heads are drained of discernible compositional or psychological purpose. Their vacant, unseeing eyes, would do nicely on the label of Rogue Dead Guy Ale.

Morandi elected boundaries that excluded competing distractions. Within the confines of a single genre his distinctiveness revealed itself and thrived. Mr. Pesce is too good a still life painter to work askance of his gifts. But then, the jarring effect of these heads might be just what he is after.

CHARLES SELIGER WAS THE YOUNGEST of the Abstract Expressionist circle that gathered around Peggy Guggenheim in the 1940s. He is now the sole survivor of the group. His creative initiative remains fertile and undiminished; his painting is more jubilant than ever — as if the lightness of being becomes more bearable with age.

|

| Elusive Blossoms, 2004 by Charles Seliger |

Rarely does any exhibition fulfill the claims made for it in a catalog essay. But Charles Seliger’s current work earns every word of praise that accompanies it. James Siena’s reaction to seeing Mr. Seliger’s painting for the first time echoes my own: “My first encounter with Charles’ work … left me dumbstruck. Here was art so personal, yet so clearly a part of Abstract Expressionism, I was embarrassed not to have seen it sooner.”

Over sixty years, Seliger has used Abstract Expressionist impulses as points of departure for an individual language that has never hardened into a mannerism. Unlike the New York School painters who sought a signature style, Mr. Seliger established his signature with size. He has kept his work to an unassuming scale, gradually reducing dimensions to the point where he can be called a miniaturist.

Immensity resides in these miniatures, as intricate as 15th century illuminated Persian manuscripts. Each panel is a Lilliputian (not much more than 12 inches square) universe of radiant, floating particles of color held in colloidal suspension. Delicate tonal gradations, created by transparent washes on gessoed panel and overlaid with fluid tracery, recall the coloristic subtleties of Klee’s “polyphonic” Bauhaus watercolors. They yield spatial depth and movement in poetic compositions that suggest — but do not depict — images viewed through an electron microscope. Or an infrared telescope, as in the haloed color-specks of “Infinite Boundaries” (2006). The quasi-scientific tendencies of the Bauhaus echo, too, in Mr. Seliger’s non-literal but clear references to the world of microscopic science.

The only valuable subject matter, insisted Mark Rothko, is that “which is tragic and timeless.” It is easier to inflate one’s own morbidities into the spirit of tragedy than to maintain vitality against the swell. Rothko committed suicide thirty six years ago, despair reinforced by a cultural climate seeking verities where they do not exist: on canvas and in the artist’s preoccupations. Charles Seliger is still creating, still celebrating worlds within a grain of sand. The last man standing, in the exultant beauty and modesty of his work, confounds the thunderous illusions that fed the Abstract Expressionist mystique.

“Victor Pesce: Paintings” at Elizabeth Harris Gallery (529 West 20th Street, 212-463-9666)..

“Charles Seliger: New Paintings” at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery (24 West 57th Street, 212-247-0082).

This review first appeared in The New York Sun, April 27, 2006.

Copyright 2006, Maureen Mullarkey